Book review: ‘Outsiders: Memories of Migration to and from North Korea’

Markus Bell writes a sobering reflection on the tens of thousands of Koreans that voluntarily left Japan for North Korea

Oliver Jia November 24, 2021

SHARE

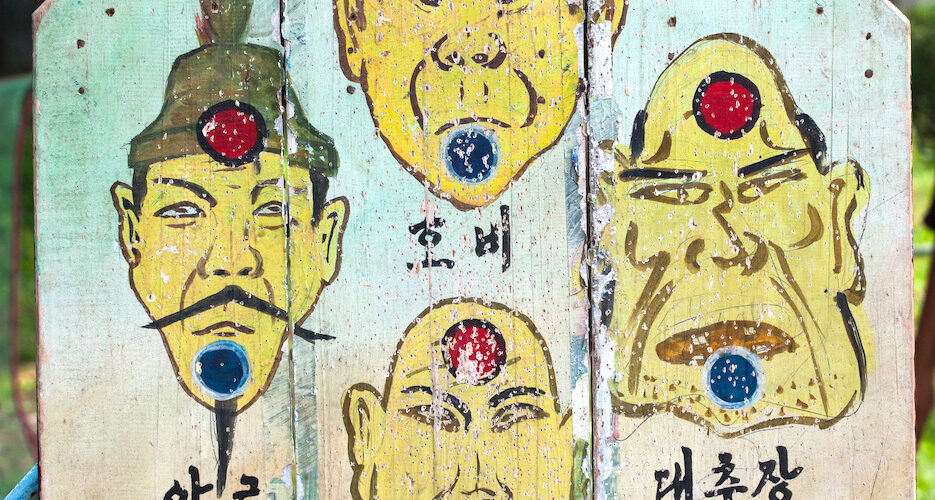

NK News (file) | Target with Japanese soldiers at Taesongsan Funfair, Pyongyang, North Korea, Sept. 7, 2008

Many are familiar with stories of North Koreans who risk their lives to escape their home country, but lesser known are the tens of thousands of people that immigrated to the DPRK from Japan, lured by promises of community and equality.

Facing discrimination and low social status in post-war Japanese society, some 93,000 ethnic Koreans voluntarily left for North Korea between 1959 to 1984. Upon arrival, most were shocked to see just how much North Korea’s communist poverty contrasted with the first world liberal democracy they had just left.

Many would weather through hardships far worse than anything they had ever experienced in Japan, and only a few were ever able to go back.

Through extensive interviews with “returnees” who left the DPRK, Latrobe University research fellow Markus Bell sheds light on the struggles of these men, women and children in his new book, “Outsiders: Memories of Migration to and from North Korea.”

While few tend to think of the reasons why one would choose to move to North Korea, the book poses complex questions and succeeds in showing that often little about the DPRK is black and white.

COMING HOME

Imperial Japan’s defeat in 1945 made the future of its former colonial subjects unclear. Voluntary and forced migration from the Korean Peninsula since the late 19th century, especially after Japan annexed Korea in 1910, meant that some 600,000 ethnic Koreans were left in Japan when the war ended.

These people were denied a pathway to citizenship in Japan after Korean independence. Many were harshly discriminated against in Japan’s homogeneous society. Bell writes that close to one in four of these so-called Zainichi Koreans relied on welfare by 1955, citing Red Cross statistics.

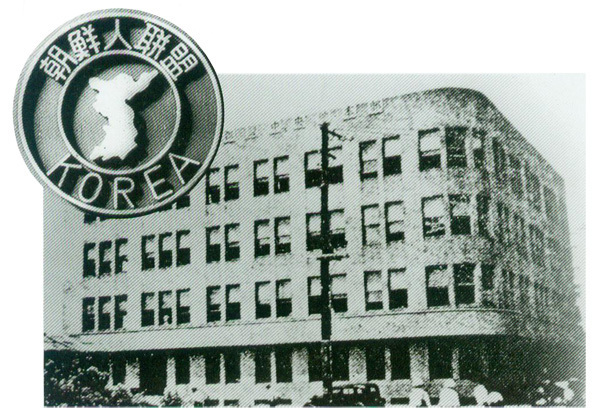

Founding of Chongryon | Image: ournation-school.com

Founding of Chongryon | Image: ournation-school.comThe status of Zainichi Koreans was politically perilous as well. The community divided itself along pro-North and pro-South ideological lines, with the DPRK-backed General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, or Chongryon, cementing itself as the most influential group.

From 1958, Kim Il Sung began advocating for a migration movement to “repatriate” ethnic Koreans from Japan back to North Korea in order to benefit his regime. Chongryon propaganda promised full DPRK citizenship, jobs, free education, state-provided housing and a monthly stipend for returnees.

These promises were highly enticing for a stateless, marginalized community. Bell points out that amid the Cold War backdrop, Japan was also eager to get rid of what it viewed to be potentially subversive elements of its society with ties to a neighboring communist nation.

Zainichi Koreans being processed before their “repatriation” to North Korea, Oct. 15, 1959 | Image: Creative Commons

Zainichi Koreans being processed before their “repatriation” to North Korea, Oct. 15, 1959 | Image: Creative CommonsStill, Tokyo solicited the Red Cross to reach out to members of the “Zainichi” community to ensure they understand what it meant to move to North Korea. Bell includes detailed stories of individuals who, after speaking with Red Cross officials, ended up staying in Japan.

Others, whether out of their own volition or pressure from Chongryon, took their entire families with them to North Korea.

ETERNAL OUTSIDERS

It soon became clear that DPRK society was never going to accept the newly arrived Koreans despite what they had been led to believe. Their association with Japan gave most a low position on North Korea’s “songbun” caste system and limited job prospects.

“We treated them like strangers,” another North Korean defector says in the book. “We treated them as if they were Japanese and there was no chance for them to become like us.”

The returnees were forbidden from speaking Japanese in public and faced difficulties adapting to North Korea’s strict rules of ideological control, self-criticism sessions and lack of freedoms compared to Japan. The 6,750 Japanese who emigrated to North Korea with their Zainichi spouses often went through the toughest difficulties as most could not speak, read or write the Korean language.

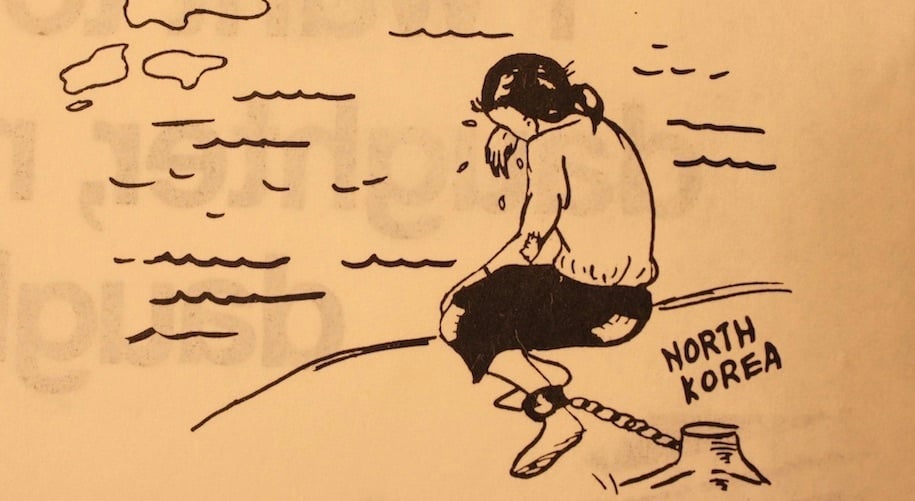

6,750 Japanese followed their Zainichi Korean spouses to North Korea, and most were unable to return to Japan. | Image: The American Committee for Human Rights of Japanese Wives of North Korean Repatriates

6,750 Japanese followed their Zainichi Korean spouses to North Korea, and most were unable to return to Japan. | Image: The American Committee for Human Rights of Japanese Wives of North Korean RepatriatesBell, however, notes that some fared better than others. Those with relatives in Japan were able to acquire goods with high resale value in North Korea such as watches, bicycles, electronics and instant noodles.

But by the time of the Arduous March famine in the 1990s, the repatriation program had long ended and relatives in Japan saw increasingly little reason to send items to family in a distant communist country they barely knew. Sanctions did little to help matters either.

Like immigrants in most countries, second and third-generation Zainichi Koreans tended to integrate better into DPRK society than their first-generation forefathers, but challenges remain. “In a sad irony, individuals who had been made painfully aware of their Korean identity in Japan were now considered too Japanese in the ethnic homeland,” Bell writes.

THERE AND BACK AGAIN

Bell brings his research back full circle by chronicling the stories of the few who managed to return to Japan from North Korea.

Unlike South Korea, which grants full citizenship to North Korean refugees, defectors in Japan are not given the same rights. The returnees who choose Japan tend to do so out of a sense of imagined familiarity.

Stories of North Korean defectors facing discrimination after settling in South Korea convince some that Japan is a better choice for a new life, according to Bell. For those with childhood memories — even vague ones — the pull to go back can be stronger than any potential economic incentives.

Yet the defectors who do make it to Japan often find themselves isolated from greater Japanese society, and the image of North Korea carries a negative stigma due to its association with sensitive political issues.

Ikuno Korea Town in Osaka, Japan | Image: Creative Commons

Ikuno Korea Town in Osaka, Japan | Image: Creative CommonsMany end up reliant on government welfare and can find nothing better than menial labor jobs. Another avenue is receiving help through Japanese humanitarian organizations specifically dedicated to aiding those coming back from North Korea.

With South Korea having been an authoritarian military dictatorship during the 1960s, politically active left-wing Japanese viewed the North as the better alternative. But once the truth of the DPRK’s political suppression and human rights violations came to light, former advocates became staunch critics of the Kim regime.

Ironically, the older leaders of these groups are typically the same individuals who pushed for repatriation to the DPRK in the first place. These humanitarian groups not only try to make amends by helping Korean returnees but by suing Chongryon and the DPRK government itself. As Bell writes though, not all refugees care about political activism.

Chongryon headquarters in Tokyo, Japan, Sept. 7, 2019 | Image: NK News

Chongryon headquarters in Tokyo, Japan, Sept. 7, 2019 | Image: NK NewsBell also makes the distinction between Koreans born in Japan who moved to North Korea and back and Koreans born in North Korea who moved to Japan for the first time.

One defector is described as attempting to pull off perfect Japanese mannerisms, but is ultimately unable to hide her North Korean background. A short visit to Seoul reveals she is similarly alienated from South Korean society, leaving her seeking a place to belong.

Another anecdote deals with an elderly returnee who searches for her childhood home near Osaka she left decades ago. Upon returning to her old neighborhood, she sees how much the landscape has changed and what little of the past remains.

It is these stories that make “Outsiders” a compelling read, adding a necessary human element that sets it apart from previous studies. If there’s any criticism to note, it’s that readers will likely find themselves wanting to hear more, with some of these anecdotes being worthy of their own standalone memoirs.

More conservative readers may also take issue with Bell’s more measured view on DPRK human rights as well as his pro-immigration proscription for Japan’s current demographic woes, but the author presents his arguments in a generally nuanced and fair manner.

Edited by Arius Derr

DEFECTOR ISSUESFOREIGN RELATIONSHISTORYHUMAN SECURITY / HUMAN RIGHTS

Oliver Jia

Oliver Jia is Social Media Editor at NK News and a Kyoto-based graduate student currently pursuing his PhD in international relations at Ritsumeikan University. His research focuses on Japan-DPRK relations and comparative foreign policy. Follow him on Twitter @OliverJia1014VIEW MORE ARTICLES BY OLIVER JIAGot a news tip?Let us know!

No comments:

Post a Comment